This tutorial is going to be off-topic compared to the others on the website. It was born out of a question regarding how to send personalized e-mails to several people on a list, and I thought it could be useful to post a tutorial online. This will help people interested in building a simple Customer Relationship Manager (CRM) and it will also show scientists that the skills they develop while working in the lab can be used in various contexts.

Let's first discuss what we want to achieve. A CRM is a tool that allows users to send e-mails to customers and keep track of their answers. It could be much more complex than that, integrating with a phone, social media accounts, billing platforms, etc. but for our purposes, we will keep it to what a normal person (like me) needs. It should be able to send the same e-mail to several people but with a certain degree of personalization, for example, saying Dear John instead of a generic Dear Customer.

The CRM should prevent me from sending the same e-mail twice to the same person and should be able to show me all the e-mails I have exchanged with that person. It should also allow me to segment customers, making it possible for me to send e-mails just to groups of people, for example, the ones who took the Python For The Lab course and those who are interested in it. The ones who bought the book and those who only asked for the free chapter, etc. Let's get started!

The Choices

First, we will need a way of sending and receiving e-mail. If you are a GMail user, you can check this guide and this other one on how to set up the server (you will need this information later on, so keep it in hand). If you want to use a custom domain to send and receive e-mail, I strongly suggest you use Dreamhost which is what I use myself (if you use the link, you will get a 50U\$ discount and at the same time you will help me keep this website running). If you expect to send more than 100 e-mails per hour, I suggest you check Amazon SES which is very easy to set up and has reasonable pricing.

Next, we need to define how to send e-mails. The fact that we are going to use Python is out of the question. But here we have several choices to make. I believe the best is to use Jupyter notebooks. They have the advantage of allowing you to run different pieces of code, see the output inline, etc. It is easier to have interaction through a Jupyter notebook than through plain scripts. Building a user interface (either a desktop app or a web app) would be too time-consuming for a minimum increase in usability.

We have now a web server, a platform, we only need to define how to store the data. For this, I will choose SQLite. I have written in the past about how to store data using SQLite, but in this article, we are going one step further by introducing an ORM, or Object Relational Mapping, which will greatly simplify our work when defining tables, accessing data, etc.

Jupyter Notebooks

If you are familiar with the Jupyter notebooks, just skip this section and head to the next one. If you are not familiar with them, I will give you a very quick introduction. First, you need to install the needed package. If you are an Anaconda user, you have Jupyter by default. If you are not, you should start by creating a Virtual Environment, and then do the following:

pip install jupyter

The installation will take some time because there are many packages to download, but don't worry, it will be over soon. Then, you can simply run the following command:

jupyter notebook

If you are not inside a virtual environment, or the command above fails, you can also try the following command, directly on your terminal:

python -m jupyter notebook

After you run the command, your web browser should open. Bear in mind that you will use as base folder the folder where you run the command above. Just select new from the top-right button and start a new Python 3 notebook.

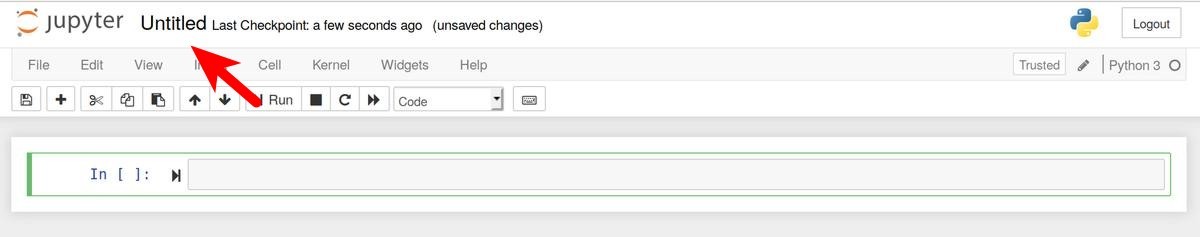

You should be welcomed by a screen like this:

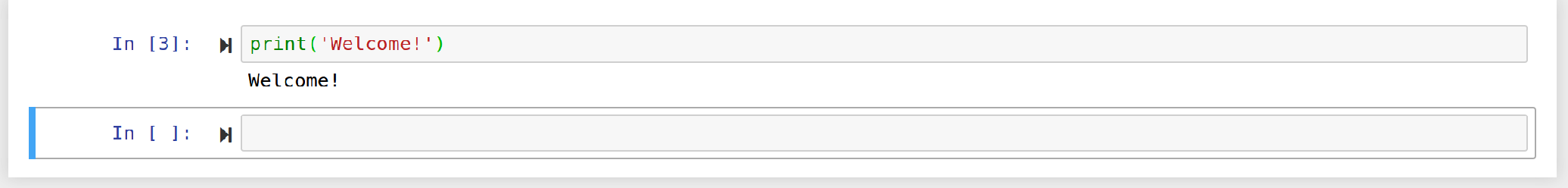

The arrow indicates the name of the notebook. You can edit it to something more descriptive than Untitled. For example, Test_Notebook. The line that you see in green is where your input should go. Let's try a simple print statement, like what you see in the image below. To run the code, you can either press Shift+Enter or click the play button that says run, while the cursor is still in the cell.

The advantage of Jupyter notebooks is that they also keep the output when you share them. You can see this example notebook on Github. And they allow you to embed markdown text in order to document what you are doing.

If you haven't used Jupyter notebooks before, now it is a great chance to get started. They are very useful for prototyping code that later can become an independent program. From now on, I will not stress every single time that the code should go into a notebook, but you should assume it.

As always, all the code for this project can be found here. The majority of the code that goes into the Jupyter notebooks can also be copy-pasted into plain Python script files. Just keep in mind that the order in which you can run cells is up to you and not necessarily from top to bottom as is the case for scripts.

Sending Email

The most basic function of any customer relationship manager is to be able to send e-mails. Having just this functionality is already useful in a lot of different situations, not only professionally but also for private tasks. For example, you can invite your friends to a party by addressing them by name: 'Dear Brian,'. In order to be able to send e-mails, you need to be able to configure an SMTP server.

If you are a Google User you can check this guide, or you can sign up to Dreamhost or Amazon Services. If you want to use a custom domain, the Dreamhost way is the easiest and quickest. You can read the documentation for configuring your e-mail.

Let's start by creating a configuration file in which we will store some useful parameters. Create an empty file in the same directory where you will be working and call it config.yml. You can use Jupyter to create this file, just select Text File after clicking on New. And in the file, put the following:

EMAIL:

username: my_username

password: my_password

port: 1234

smtp_server: smtp.server

The format of this file is called YAML, which is a very simple markup

language in which blocks are indented by 2 spaces. Replace the

different variables by what you need, i.e., replace my_username with

the username of your server, etc. My choice of putting this information

on a different file is that now I can share my Jupyter notebooks without

exposing my password. In order to work with YAML files in Python, you

will need to install pyyaml:

pip install pyyaml

Now we are ready to start. Let's create a new Python notebook. Let's call it, for example, simple_crm. The first thing to do is to load the configuration:

import pyyaml

with open('config.yml', 'r') as config_file:

config = yaml.load(config_file)

If you are not familiar with the with command you can check this

article about the context manager. If you want

to explore how your variable config looks like, you can simply write

it in a different cell and press Ctrl+Enter. The result is a dictionary

with the needed parameters for sending e-mail. So, let's get to it.

First, let's compose a short message and subject:

msg_sbj = 'Testing my brand new CRM with Jupyter notebooks'

msg_text = '''This is the body of the message that will be sent.\n

Even if basic, it will prove the point.\n\n

Hope to hear again from you!'''

Now, the way of composing the message requires to import a special

module of Python called email. The code would look like this:

from email.mime.multipart import MIMEMultipart

from email.mime.text import MIMEText

me = "Aquiles <my@from.com>"

you = "Aquiles <your@to.com>"

msg = MIMEMultipart()

msg['From'] = me

msg['To'] = you

msg['Subject'] = msg_sbj

msg.attach(MIMEText(msg_text, 'plain'))

We first create a msg, which will be ready to send both plain and HTML

e-mails. We specify the from, to, and subject of the email.

Remember that if you specify the wrong from, your message has a high

chance of being filtered either by your SMTP provider or the receiver's

server as spam. Be sure you use the proper e-mail from-address that you

have configured.

The last line attaches the plain version of the e-mail to the message. We will see that it is also possible to send more complex messages, with a plain text version and an HTML version. Now that we have our e-mail ready, we need to send it.

import smtplib

with smtplib.SMTP(config['EMAIL']['smtp_server'], config['EMAIL']['port']) as s:

s.ehlo()

s.login(config['EMAIL']['username'],config['EMAIL']['password'])

s.sendmail(me, you, msg.as_string())

s.quit()

First, you see that we start the SMTP connection using the configuration

parameters that were defined on the config.yml file. The ehlo

command is a way of telling the server hello and start the exchange of

information. We then log in and finally send the message. See that we

defined both the sender and receiver twice: they are used in the

sendmail command, but also they are defined within the msg object.

If you used real e-mails, you should by now receive the example message.

Warning

Sometimes GMail does not deliver messages that you send to yourself from different aliases. If nothing arrives, you can try to send an e-mail to a different address which you control.

Now, imagine you would like to personalize the message before sending it. For example, we would like to address the recipient by name. We can improve our message, to make it look like a template, like this:

msg_text = '''Hello {name},

This is the body of the message that will be sent.

Even if basic, it will prove the point.

Hope to hear again from you!'''

And you can use it like this:

msg_text.format(name='Aquiles')

Which will output the message exactly as you expected. If you now would like to send a message to different people, you could simply do a for-loop. Remember that before generating the message body, you replace the name by the name of your contact as shown in the code above.

Note

I will not go into the details of how to implement the loop because we will work on this later on, in a much more complete solution.

Adding HTML to the message

Now it is time to make your messages more beautiful by adding HTML to them. Coding HTML e-mails is a complicated subject because there are many things to take into account. First, e-mail clients work differently from each other, meaning that the way your e-mail is displayed depends on how it is opened. Screen sizes change, and therefore your e-mail should have a fixed width or it will look very ugly on some devices. Being aware of these problems, I would suggest you check ready-made templates developed by designers who took care of all of this.

In this tutorial, we are going to use Cerberus which, among other things, is open source and free. If you unzip the contents, you will find 3 important files: cerberus-fluid.html, cerberus-responsive.html, and cerberus-hybrid.html. Those are three different templates which you can use. We are going to use the responsive version.

You should open the files with your browser in order to have an idea of how they look. Also, check the source code to understand how you can utilize different elements, change the color, etc. The documentation is your best friend. I have stripped down a bit the template. You can find it here. For practical purposes it doesn't really matter, you can use the original also.

What we will do is keep the e-mail template as a separated file, so we don't pollute the notebook that much. In order to add it to our message, we need to do the following:

with open('base_email.html') as f:

msg_html = f.read()

And then, the only two things we need to add to the message is the following:

msg = MIMEMultipart('alternative')

msg.attach(MIMEText(msg_html, 'html'))

Pay attention that we need to initialize the message with the argument

'alternative'. If we fail to do this, the message will include both

the text and the HTML versions one after the other.

The idea of attaching both the text and the HTML version of the e-mail is that we keep in mind that not all people accept HTML messages. You can configure most e-mail clients to use only plain text messages. This is a good way of preventing trackers from spying on you and makes e-mails easier to read. Moreover, it can make phishing attempts easier to spot.

The e-mail, if you attach both versions, will be shown as HTML if the client supports it and will fall back to the text version if it doesn't. In general lines, we can say that adding HTML versions of your messages is up to you, adding the text version should be mandatory.

Receiving Email

Sending e-mails is half of what a CRM should do. The other half is checking e-mails. This will allow the system to store messages associated with the people with whom you interact. This will allow you to check, for example, who never replied to your questions. We will start by updating the configuration file since we now need to add the POP3 server:

EMAIL:

username: my_username

password: my_password

port: 1234

smtp_server: smtp.server

pop_server: pop.server

If you would need a different username or password for the POP server, you can add them also to the config file. Remember that you will need to reload the configuration file in order to have the new variable available.

Reading from the server is relatively easy:

import poplib

server = poplib.POP3(config['EMAIL']['pop_server'])

server.user(config['EMAIL']['username'])

server.pass_(config['EMAIL']['password'])

If you run the block again and it works out correctly, you will see the following message:

b'+OK Logged in.'

Now we need to download the list of messages that are available on the server:

resp, items, octets = server.list()

Bear in mind that if there are no messages available, you won't be able

to do anything else. You can always send one or more e-mails to yourself

in order to test the code. Items will hold information regarding the

available messages. If you explore the items variable, you will see an

output like the following:

[b'1 34564', b'2 23746', b'3 56465']

In this case, the server has 3 available messages. The first number is the id of the message, while the second is its size. If we want to retrieve the first message, for example, we can do the following:

msg = server.retr('1')

If you explore the msg, you will see it is a tuple with 3 elements.

The message itself is stored in msg[1]. However, it is a list, full of

information regarding the message you have downloaded. Without going

into too much detail, first, you need to transform the list into a

single array, and then we can use the mail tools to parse the

information into a usable format:

import email

raw_email = b'\n'.join(msg[1])

parsed_email = email.message_from_bytes(raw_email)

You are free to explore each step independently to try to understand

what is available in your message. The parsed_email has a lot of

information, not only regarding who sent the message and to whom but

also the server used, spam filtering options, etc. We would like to show

the contents of the e-mail, both the HTML and the text formats, so we

can do the following:

for part in parsed_email.walk():

if part.get_content_type() == 'text/plain':

print(part.get_payload()) # prints the raw text

This will go through all the available information in the message, and

if it finds it is of type text/plain, it will print it to the screen.

You can change it to text/html and it will show the other version, if

available.

As you can see, retrieving e-mails is relatively more complex than sending e-mails. There are also some other concerns regarding what you do with the messages you downloaded. For example, you can leave them on the server, thus they will be available from other clients as well. You can also choose to delete them from the server after reading, etc. Each pattern has advantages and disadvantages, so that will be up to the workflow you are considering.

The code up to here can be found on this notebook. Now we are going to focus a bit more onto expanding the usability of our tools.

Using a Database

In the previous sections, we have seen how you can send and receive e-mails with Python directly from a Jupyter notebook. Now it is time to focus onto a different topic. It is important when you want to establish relationships with customers, to have a way of storing information persistently. For example, you would like to keep an agenda of contacts, you would like to know when was the last time you contacted someone, etc.

In order to achieve a high level of flexibility, we are going to use a database to store all our information. Fortunately, Python supports SQLite databases out of the box. We have discussed about them in a different article that may be useful for you to check if you want to dig into the details. We are going to use a library called SQLAlchemy, which will allow us to define relationships between elements much faster. You can install it like any other Python package:

pip install sqlalchemy

The first thing we will do is creating a new notebook to explore how to use the database from within Jupyter. Let's start by importing all the needed modules:

from sqlalchemy import create_engine

from sqlalchemy import Column, Integer, String

from sqlalchemy.ext.declarative import declarative_base

Next, we create the database engine:

engine = create_engine('sqlite:///crm.db', echo=True)

Note that the engine supports other types of databases, not only SQLite. However, SQLite is by far the easiest to work with for small applications such as ours.

We also define a declarative base, that will allow us to define classes that will be mapped to tables:

Base = declarative_base()

Now it is time to define what information we want to store to the database. For the CRM it seems reasonable to start by defining customers. The advantage of using SQLAlchemy is that instead of working directly on the database, we can do that through the engine and the base. To define what information we want to store, we have to define a class:

class Customer(Base):

__tablename__ = 'customers'

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

name = Column(String)

last_name = Column(String)

email = Column(String)

def __repr__(self):

return "<Customer(name='{}', last_name='{}', email='{}')>".format(

self.name, self.last_name, self.email)

I think the code above it is self-explanatory. We define the name of the

table we want to use. Each attribute defined with Column will be

transformed into a column in the table, of the specified type, in our

case we have Integer for id and String for all the rest. In order

to create the table, we have to run the following command:

Base.metadata.create_all(engine)

You will see a lot of content appearing on the screen. If you are

familiar with SQL you will notice the commands that are being executed.

Now what we have is a very nice relationship between a class

(Customer) and a table (customers) on our database. Let's create our

first customer:

first_customer = Customer(name='Aquiles', last_name='Carattino', email='aquiles@uetke.com')

And now we need to add it to the database. This is achieved through the creation of a session:

from sqlalchemy.orm import sessionmaker

Session = sessionmaker(bind=engine)

session = Session()

The last step is to add the customer to the database:

session.add(ed_user)

session.commit()

And that is all. If you know how to explore the database with an

external tool, you will see the data that we have just added. You can

follow the steps above for as many customers as you want. To retrieve

information from the database, we can use the session and the Customer

class directly. For example:

one_customer = session.query(Customer).filter_by(name='Aquiles').first()

print(one_customer)

It will give you as output the information of your customer. Pay attention to the fact that when you filter in this way, the options are case sensitive. We will not cover all the details regarding how to use SQLAlchemy, especially because their documentation is very extensive, but it is important to see how to search with partial information, for example looking by parts of the name:

one_customer = session.query(Customer).filter(Customer.name.like('aqui%')).first()

This will find all customers with a name that starts with aqui,

regardless of their case. There is a detail that it is also very

important and that I haven't mentioned yet, the first() that appears

at the end. Let's see what happens if you have two customers in the

database, and they have similar names so that the command above gets

both of them:

second_customer = Customer(name='Aquileo', last_name='Doe', email='aquileo@doe.com')

session.add(second_customer)

session.commit()

Let's remove the first(), and let's run the same command as before:

answer = session.query(Customer).filter(Customer.name.like('aqui%'))

print(answer)

Will give you as output:

<sqlalchemy.orm.query.Query at 0x7f003da05390>

The answer is not a list of customers, but an object called Query. If you want to go through each element, you can do the following:

for c in answer:

print(c)

The idea of the query is that it knows how many elements are there but it didn't load the information to memory. This makes it incredibly handy if you are working with very large databases.

With a bit of creativity, you can already merge what we learned before in order to send e-mails to all the customers in your database. Before discussing how to implement that, I would like to focus on one more topic, which is how to add tags to the customers and keep track of the sent messages.

Database Relationships

One of the features we want to have in our CRM is to be able to keep

track of the sent messages, so we can avoid sending twice the same

e-mail to the same person, or we can check how long it was since we sent

the last message, etc. We will define a new class called Message in

which we will hold the information of every message sent. It will look

like this:

from sqlalchemy import Text, Date, ForeignKey

from sqlalchemy.orm import relationship

class Message(Base):

__tablename__ = 'messages'

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

name = Column(String)

text = Column(Text)

date = Column(Date)

customer_id = Column(Integer, ForeignKey('customers.id'))

customer = relationship("Customer", back_populates="messages")

def __repr__(self):

return "<Message(name='{}', date='{}', customer='{}')>".format(

self.name, self.date, self.customer)

Bear in mind that the imports complement the ones of the previous

section, they do not replace the others but are new for this piece of

code. The beginning is very similar to the previous class, but the main

difference is the part referring to the customers. Each message will be

sent to a specific customer. To make this bridge, we use the

ForeignKey. This means that the value that is going to be stored in

customer_id has to be an existing customer id. In this way, we can add

more dimensions to our plain tables.

The relationship is a way of telling SQLAlchemy where the data is

going to be accessed. Having the id of the customer is handy, but it is

better if we have direct access to the information. In such a case, if

we would like to know the name of the customer who got the message, we

can do something like message.customer.name. The opposite relationship

is also valid, and we need to add it. We can simply do:

Customer.messages = relationship('Message', order_by=Message.id, back_populates='customer').

And then you just need to update the engine:

Base.metadata.create_all(engine)

Now, let's create some messages to understand how we can use this new strategy. We first need to get at least one customer, so we can assign the messages to it:

from datetime import datetime

c = session.query(Customer).first()

new_message = Message(name='Welcome', text='Welcome to the new CRM', date=datetime.now(), customer=c)

session.add(new_message)

session.commit()

We get the first customer from the table, and then we create a new

message. This is just an example, but in principle, the variable text

could be much longer. If we want to retrieve this message from the

database, we can do the following:

message = session.query(Message).first()

print(message)

And now you will see that you have the information not only about this message but also about the customer to whom the message was sent. You can also try the other way around, see all the messages sent to a particular customer, by doing the following:

c = session.query(Customer).first()

print(c.messages)

And you will get a list of all the messages that were sent. Now you have an idea of how this can very quickly start to be a useful tool, not just a mere exercise.

The relationship between messages and customers is called many-to-one because a customer can have many messages associated with it, but each message will be associated with a single customer. There is also another relationship possible, which is called many-to-many. This would be the case of having lists of customers. A customer can belong to several lists, and at the same time, each list can contain several customers.

If you think that a database is nothing more than a collection of tables in which each entry has a unique identifier, you will realize that there is no way of making this many-to-many between two tables directly. We will need to define an intermediate table which will hold these relationships. First, let's start by the list itself:

class List(Base):

__tablename__ = 'lists'

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

name = Column(String)

Base.metadata.create_all(engine)

And now we need to create the intermediate table:

from sqlalchemy import Table

association_table = Table('list_customer', Base.metadata,

Column('left_id', Integer, ForeignKey('customers.id')),

Column('right_id', Integer, ForeignKey('lists.id'))

)

Base.metadata.create_all(engine)

See, that it is a table that has two columns each with a foreign key, one for the customer and one for the list.

We can do the same we did earlier in order to be able to use

customer.lists to get the lists to which the customer is subscribed:

Customer.lists = relationship("List",

secondary=association_table,

backref="customers")

Base.metadata.create_all(engine)

And now, it is time to create a list, append a user and save it:

c_list = List(name='New List')

customer = session.query(Customer).first()

c_list.customers.append(customer)

session.add(c_list)

session.commit()

Remember not to use a plain list variable, since it is a Python

keyword. I think it is pretty clear what is going on. Finally, if you

want to retrieve a list and find the customers subscribed to it, you

would do:

las_list = session.query(List).first()

print(las_list.customers)

On the other hand, you can check the lists to which a user is subscribed:

print(customer.lists)

See that the output of this last command is not particularly nice. This

is because we haven't defined a specific __repr__ method as we have

done for the other classes.

With this, we are done regarding how to use databases to store information. Now it is time to get into the action. The full code discussed in this section can be found on this notebook. Now it is time to clean up the code in order to make more usable and extendable.

Sending To All Customers

The notebook that we have developed in the previous section is very dirty. We have been adding features on the fly, without really worrying about how easy it is to understand it. Imports were scattered all over the place, classes get modified at runtime, etc. An example of a cleaned up notebook can be found here. I won't enter into the details, you are free to use it.

We are going to focus now a bit more on usability. How can we send the e-mail to all our customers, using what we've learned in the first section and combining it with what we've developed in the previous one? We will start a new notebook. The first thing we need is to have available all the classes to interface with the database. We start the new notebook like this:

%run clean_db.ipynb

in this case, you need to change clean_db by whatever name you have

given to the notebook that created the database. The command above is

equivalent to inserting the notebook at the beginning and running it.

Therefore, all the variables, classes, functions, etc. that you have

developed are going to be available.

Now we need to be able to send a message to all our customers. We can develop a function that will take care of the sending of e-mails:

def send_all():

customers = session.query(Customer)

for customer in customers:

message = customer.create_msg('Message_name', 'template_file')

message.send(config)

session.add(message)

session.commit()

At this stage this is not sending any message, it is just showing how it

would look like. The code above implements a lot of different choices on

how to find a solution. One is that we would like the Customer class

that creates a message, and the message is able to send itself. Then we

store that message into the database. This prevents adding messages to

the database if the sending fails. The Customer class will look like

this:

class Customer(Base):

__tablename__ = 'customers'

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

name = Column(String)

last_name = Column(String)

email = Column(String)

def create_msg(self, message_name, template_file):

with open(template_file, 'r') as template:

text = template.format(name=self.name)

message = Message(name=message_name, text=text, customer=self, date=datetime.now())

return message

def __repr__(self):

return "<Customer(name='{}', last_name='{}', email='{}')>".format(

self.name, self.last_name, self.email)

You see that we have only added the method create_msg which returns a

new message, after formatting the test. Then, we need to update the

message class to be able to send itself to a customer. We can do the

following:

class Message(Base):

__tablename__ = 'messages'

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

name = Column(String)

text = Column(Text)

date = Column(Date)

customer_id = Column(Integer, ForeignKey('customers.id'))

customer = relationship("Customer", back_populates="messages")

def send(self, config):

me = config['me']

you = '{} <{}>'.format(self.customer.name, self.customer.email)

msg = MIMEMultipart('alternative')

msg['From'] = me

msg['To'] = you

msg['Subject'] = self.name

msg.attach(MIMEText(self.text, 'plain'))

with smtplib.SMTP(config['EMAIL']['smtp_server'], config['EMAIL']['port']) as s:

s.ehlo()

s.login(config['EMAIL']['username'],config['EMAIL']['password'])

s.sendmail(me, you, msg.as_string())

def __repr__(self):

return "<Message(name='{}', date='{}', customer='{}')>".format(

self.name, self.date, self.customer)

You can see that I have moved the me option into the config file. This

is something you will need to add by yourself in order to make it

compatible. It should look like:

me: My Name <my@email.com>

And should be top-level (i.e. not inside the EMAIL block). Since

sending the message needs to have the config available, we will run the

code like this:

with open('config.yml', 'r') as config_file:

config = yaml.load(config_file)

send_all()

Remember that when you change notebooks you need to save them, and then

you need to run the first block with the %run command again in order

to reflect the changes. We still need to work a bit on the send_all.

In the example above, we have fake names for the subject and the

template. We can improve that:

def send_all(subject, template):

customers = session.query(Customer)

for customer in customers:

message = customer.create_msg(subject, template)

message.send(config)

session.add(message)

session.commit()

print('Sent message {} to: {}'.format(subject, customer.email))

Now, let's create a text file called test_email.txt with the following content:

Hello {name},

Welcome to the test CRM.

Hope you are enjoying it!

And now, if we want to send the message to all our customers, we can do the following:

with open('config.yml', 'r') as config_file:

config = yaml.load(config_file)

send_all('Testing the CMR', 'test_email.txt')

And now, you should see your messages being sent. You should also see that the messages are personalized, replacing the name in the template by the name of the customer getting the message. You can get as creative as you want with these options. However, there is still an important feature missing: send to a group of customers.

Refactoring: Send to a list

Since the amount of code we have developed is not that much, you can

still go through it and change it in all the needed places. But imagine

someone else has developed code that depends on what you have done. If

you change something as important as the number of arguments a function

takes, you will break the downstream code. In our case, we want to

change the send_all function in order to accept the name of a list as

an argument. However, we don't want to break the code that already uses

send_all with just two arguments (subject and template).

If you want to add a new argument to a function while making it

optional, there are two ways. One is to use the *args syntax, the

other is to use a default value. The latter is slightly easier to

understand for novice programmers. If we do the following to our

function:

def send_all(subject, template, list_name='all'):

You will see that the code

send_all('Testing the CMR', 'test_email.txt') still works fine. So we

can now improve the function to get the customers that belong to a

certain list.

def send_all(subject, template, list_name='all'):

if list_name == 'all':

customers = session.query(Customer)

else:

customer_list = session.query(List).filter_by(name=list_name).first()

customers = customer_list.customers

for customer in customers:

message = customer.create_msg(subject, template)

message.send(config)

session.add(message)

session.commit()

print('Sent message {} to: {}'.format(subject, customer.email))

So now, if you create a list of customers named 'Initial Customers',

for example, you can send a message to them by simply doing the

following:

send_all('Testing the CMR', 'test_email.txt', 'Initial Customers')

Avoid repeating messages

What you have seen up to now, should open the doors to a lot of very

nice creative approaches not only to CRM but to a variety of tasks that

you can automate with Python. The last feature that I would like to show

you is how to avoid sending the same message to the same person. You can

check it either when you create the message with the customer class, or

before sending it. Since it is normally a good idea to catch problems as

early as possible, let's improve the Customer class:

class Customer(Base):

__tablename__ = 'customers'

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

name = Column(String)

last_name = Column(String)

email = Column(String)

def create_msg(self, message_name, template_file):

message_count = session.query(Message).filter_by(name=message_name, customer=self).count()

if message_count > 0:

raise Exception('Message already sent')

with open(template_file, 'r') as template:

template = template.read()

text = template.format(name=self.name)

message = Message(name=message_name, text=text, customer=self, date=datetime.now())

return message

The highlighted line is the important change to the Customer class.

Pay attention to the syntax. We filter both by the message name and the

customer who received the message. Then, we use the count() method,

which is the proper way of knowing how many results are available in the

database. It is much more efficient than getting all the results with

all() and then using the len() function. Anyways, if you try again

the send_all function, you will see that it fails if you try to send

the same message twice. Now, this is not exactly what we need. If you

want to send the message to the people who didn't get the message yet,

you would like to skip the people, not stop the execution.

In order to achieve that, we can handle the exception. But since we are using a generic exception, we will handle everything in the same way, regardless of whether it was raised because of an error in the database or because the message was repeated. The best strategy is therefore to create a custom exception:

class MessageAlreadySent(Exception):

pass

And then the Customer can use:

if message_count > 0:

raise MessageAlreadySent('Message {} already sent to {}'.format(message_name, self.email))

Finally, we can change the send_all in order to catch this specific

exception:

def send_all(subject, template, list_name='all'):

if list_name == 'all':

customers = session.query(Customer)

else:

customer_list = session.query(List).filter_by(name=list_name).first()

customers = customer_list.customers

for customer in customers:

try:

message = customer.create_msg(subject, template)

message.send(config)

session.add(message)

session.commit()

print('Sent message {} to: {}'.format(subject, customer.email))

except MessageAlreadySent:

print('Skipping {} because message already sent'.format(customer.email))

If the exception is MessageAlreadySent we will deal with it and will

skip the user. Bear in mind that since the exception appears with the

customer.create_msg line, the rest of the block is not executed, the

message is not created, nor added to the database. This guarantees that

if the exception is of a different kind, for example, the SMTP server is

not working, the database is broken, etc. the exception will not be

handled and the proper error will appear on the screen.

The final version of the definition of classes can be found on this notebook, while the final version for the sending e-mail is this notebook.

Conclusions

This tutorial aims at showing you how you can quickly prototype solutions by using Jupyter notebooks. They are not the proper tool if you want to distribute the code as a package for others to use, but it is very quick to find problems, run just what you need, etc.

Regarding the CRM itself, it is not complete yet. You can see it as a minimum-viable-product. You can send e-mails to your customers, keep track of what messages were sent when etc. Considering the amount of work it took to set it up, you should be very satisfied.

The main objective of this tutorial was to show you how you can combine different tools in order to build a new project. Of course, many things can be improved, made more efficient, etc. The reality is that if you need to handle communication with some hundreds of customers, you don't need much more than what we did. Perhaps you can make it more functional, prettier, etc. But that is more customization than core development.